- Vabamu Exhibitions abroad

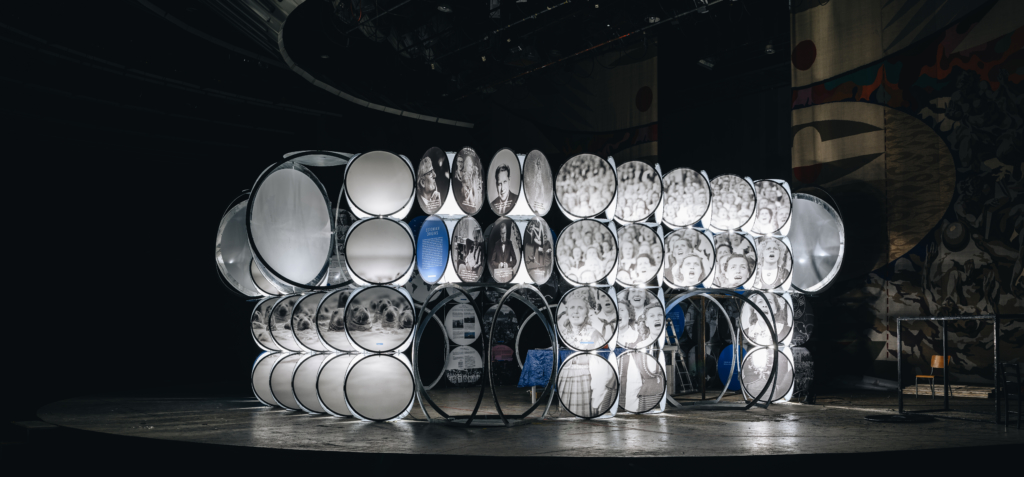

Masters of Our Own Homes: Estonia at 100

The exhibition was open in various locations from May 2018 to July 2019

The purpose of the travelling exhibition, “Masters of Our Own Homes: Estonia at 100” was to commemorate a century since the founding of the Republic of Estonia. It was also to introduce Estonian history, culture, innovation, and, most of all, its people, to the wider world.

The locations of the exhibition were Stanford (31 May – 6 June 2018), Toronto (27 September – 5 October 2018), Boston (27 October – 27 November 2018), Chicago (30 May – 5 June 2019) and Washinton (June – July 2019).

The exhibition was divided into 5 sections:

1. History

The establishment of the Republic of Estonia, secured by a 1920 treaty with Russia, seemed to cap the Estonians’ long struggle to manage their own affairs. For the next two decades, it appeared as if they had achieved just that as the country marched into the modern age with all its luxuries.

As Europe disintegrated into armed conflict in 1939, Estonia was occupied by the Soviets, then the Nazis, then the Soviets again. Savagery and brutality spread across the land. Some Estonians were deported to Siberia, others were interned and massacred by Hitler’s forces. Thousands piled into boats to flee, while resistance fighters called Forest Brothers hid in the woods.

In 1991, amidst chaos in Moscow and a resurgence in national pride epitomized by events like the Singing Revolution and the Baltic Way, Estonia reaffirmed its independence and set out on a new course: transforming itself into the one of the freest and most innovative countries in the world.

2. Culture

Estonian culture is diverse and rich. Whatever the context — be it music, theater, fashion, or sport — the Estonians have applied their austere northern perspective with spectacular and often haunting results. This curious magic manifests itself in everything from the sparse minimalist style of Arvo Pärt, perhaps the most revered living classical music composer, to the heroics of Olympic gold medalists like cross-country skier Kristina Šmigun-Vähi or discus thrower Gerd Kanter, or the appetizing New Nordic Cuisine dishes of beetroot, white fish, and potatoes that bubble and simmer in the country’s trendiest cafe kitchens.

3. Innovation

The Estonians’ love for efficiency found a natural output in doing almost everything online, and the first letter of the country’s name — E — seemed oddly prophetic, as people began to talk about an “e-Estonia” phenomenon. So when Trevor Noah, host of The Daily Show, asked then Prime Minister Taavi Rõivas in 2016 if it was possible to pay taxes online in five minutes he was swiftly corrected. ” It used to be,” Rõivas told Noah. “Now it’s three minutes on average.” The Estonians’ entrepreneurial, self-sufficient spirit has also manifested itself in a bevy of world-class startups that have changed the way people communicate, such as Skype, or transfer money, such as TransferWise, leading global tech industry observers to dub the country “the next Silicon Valley.”

4. Our people

Restless and peaceful, ambitious and cool-headed, rustic and tech-savvy: the Estonian people are the sum of their contradictions. At first glimpse, they may appear to be stereotypical northerners, quiet and thoughtful, slow to speak, easy does it, no need to hurry. Even the urbanites will tell you they prefer nothing more than to escape to the quiet idyll of a country house or a seaside cottage. In winter, they race each other on skis, in summer, they fan out across the land like busy ants. The roads are backed up with construction work and the long days parade by with a relentless agenda of festivals, concerts, and gatherings. On the summer solstice, the Estonians congregate around bonfires and snap photos with their smartphones.

For these insatiable people, life is to be lived, and not a second of it to be wasted.

5. Estonian Origins

Emigration from Estonia began already in the Tsarist era and continues to this day, but the greatest number of Estonians left their home country during the Second World War. Some fled in boats to Sweden, others traversed the frozen sea to Finland, and others found themselves in refugee camps across Europe, from which they headed to Canada, the United States, Australia, and even South America. Many of them landed in these new lands with literally nothing, but quickly built themselves up into artists, architects, and entrepreneurs so well-known that few would guess at their Estonian origins.

Thank you:

Estonia 100; Hasartmängumaksu Nõukogu; Eesti Kultuurkapital; Hanna Linda Korp; Justin Petrone; Triin Kõrge; Motor, Helen Paat, Jaak Prints; Stanford University Libraries, Liisi Esse; Embassy of the Republic of Estonia Washington, D.C., Kairi Saar-Isop; Estonian Studies Centre/VEMU: Museum of Estonians Abroad, Piret Noorhani; The Baltic American Society of New England; The Boston Estonian Society; Anne-Reet Annunziata; Mart Ojamaa; Annika Haas; Birgit Püve; Nele Tasane; Kaupo Kikkas; Stina Kase; Sven Zacek; Tõnu Runnel; Tõnu Tunnel; The National Archives of Estonia; Sports and Olympics Museum; The Art Museum of Estonia; Estonian National Museum; Tallinn City Museum; Tartu City Museum; Järvamaa Museum; Aivo Põlluäär; Laura Jamsja; Tanel Eero; Eva-Liisa Roht-Yilmaz; Tarmo Haud; Maaeluministeerium; Karel Kravik; Anu Vahtra

Back

Back