Lisa Trei:

Working at Vabamu this spring as a Fulbright Specialist has given me the opportunity to combine my professional experience as a writer and my personal interests as an Estonian-American. I deeply support the museum’s mission to educate visitors about Estonia’s history and its struggle for independence, and its ongoing efforts to remain free and secure forever. In the wake of Russia’s brutal aggression in Ukraine, Vabamu’s work is more important than ever.

My grandparents emigrated to America in the 1920s when Estonia was a free country. My father was born in New York City and, unlike most children of emigres my age, I did not grow up hearing Estonian. To me, Estonia was a far-off, mystical land where people wore folk costumes and spoke an unintelligible language. It was only when our family visited Tallinn for the 1985 Laulupidu that I discovered Estonia was a real place. In spring 1990, Marju Lauristin spoke at Columbia University and afterwards invited me to teach “practical journalism” at Tartu University. I was an ambitious reporter eager to cover the crumbling Soviet empire for U.S. newspapers from Tallinn, not Moscow, where most U.S. correspondents were based. In October 1990, I moved to Tartu to teach and also started working for The Estonian Independent, a scrappy English-language weekly in Tallinn.

The revolutionary events of 1991 pushed the backwater Baltic states onto the front pages of newspapers around the world. For six years I covered the region for many U.S. newspapers and magazines, including the Wall Street Journal. During that time, I acquired an Estonian passport and met my future husband.

In 1996, we left Estonia for California, and I began working in communications at Stanford University. The Bay Area Estonian community was changing as World War II-era refugees passed away and post-independence Estonians—first young adventurers and then IT entrepreneurs—began arriving in Silicon Valley. In 2017, a small group of us thought it would be fun to sing in the Laulupidu rather than just watch it as tourists. We formed the San Francisco Community Choir and, after a lot of work, we were accepted. It was incredible singing “Ta lendab mesipuu poole” alongside thousands and thousands of Estonians and I realized I wanted to spend more time here.

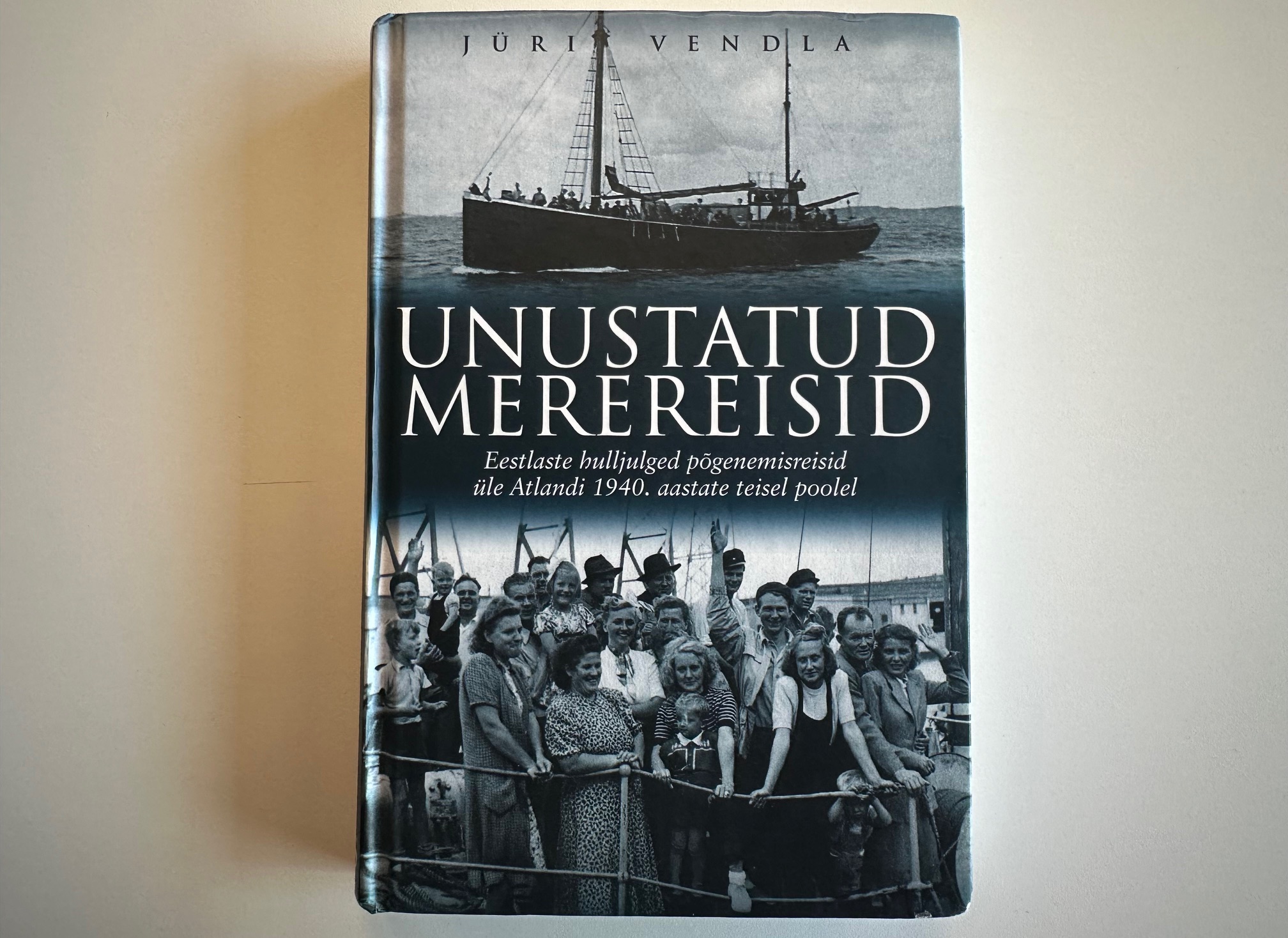

After retiring from Stanford last year, I applied to Tallinn University to pursue a master’s degree in Estonian Studies. In addition to improving my language skills, I wanted to translate into English Unustatud merereisidby Jüri Vendla, a book about Estonian refugees who escaped from Sweden in the late 1940s and sailed across the Atlantic in small boats because they feared they would be sent back to Soviet-occupied Estonia. My late father, Alan Trei, had started writing a novel about one of the boats, the Erma, and his research is included in Vendla’s book. When the master’s program was suddenly canceled, Ede Schank Tamkivi and Kadri Paju, whom I had met at Stanford, suggested that I apply for a Fulbright Specialist position at Vabamu. Given Stanford’s close connection with the museum, the fellowship has been a natural fit. Apparently, it’s the first time a Fulbright Specialist has been placed with a museum and I hope my successful experience here will open doors for many others. In addition to consulting on communications and fundraising, I am developing a digital exhibit based on Unustatud merereisid that will launch this fall to coincide with the 80thanniversary of the Suur Põgenemine.

Vabamu is so much more than a museum filled with old things. Its young and dynamic staff work incredibly hard to connect the museum’s mission with the interests and concerns of Estonian society today. Beyond guided tours and special exhibits, there are public talks by academics, politicians, and activists, educational tours for high school students, teacher training sessions, and free online courses. Staff organize bespoke visits for international guests and convene meetings to advance business partnerships. The goal is to help more people feel connected to and invested in Estonia and its future as a free, democratic nation. I am privileged to make a small contribution to this effort.

Pictures below:

-

Lisa Trei and her daughters at the 2019 Laulupidu

-

Lisa and her grandmother, Alice Trei, circa 1985, outside the family’s apartment building in New York City that housed many former Estonian DPs.

-

Unustatud merereisid/ Forgotten Sea Journeys by Jüri Vendla